slug: cross-chain-asset title: Enabling Cross-Chain Asset Exchange On Permissioned Blockchains author: Yining Hu, Ermyas Abebe, Dileban Karunamoorthy, Venkatraman Ramakrishna author_title: Contributors author_url: https://hyperledger-labs.github.io/weaver-dlt-interoperability/

tags: [enterprise, interoperability, asset-exchange]

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a growing demand for enabling interoperability across independent blockchains. Cross-chain asset exchange is a significant step towards blockchain interoperability. For public blockchains, the most popular application for asset exchange is cryptocurrency exchange. For permissioned blockchains, cross-chain asset exchange can be useful in Delivery Versus Payment (DvP) and cross-border payment scenarios. There exist various protocols designed for asset exchange on public blockchains. However, a widely adopted standard for designing such protocols for permissioned blockchains still does not exist. Moreover, most existing protocols are designed for public blockchains and their suitability to be applied to permissioned blockchains is unclear.

In this article, we aim to lay out a set of requirements for designing cross-chain asset exchange protocols between permissioned blockchains. First we present a canonical motivating use case and then list the various patterns that such cases will follow in real-life scenarios. We then present a short survey of existing cross-chain exchange protocols for public blockchains, following which we summarise the building blocks, core mechanisms and security properties commonly involved in the protocol designs. We then analyse the requirements imposed by permissioned blockchains in comparison to public blockchains, and discuss the additional properties with respect to these restrictions.

Motivation and Use-case

In traditional financial markets parties trade assets such as securities and derivatives for cash or other assets. To reduce risk, various clearing and settlement processes and intermediaries are often involved. One form of settlement is a DvP where the transfer of securities is performed only in the event of a corresponding payment. This arrangement reduces principal risk by ensuring that both parties receive their end of the exchange. However, settlement in financial markets are slow and time consuming. It also involves counterparty risks and requires intermediaries.

Over the past few years, we have been seeing significant efforts in digitising and tokenising both currencies and securities on Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) infrastructures. On the one hand we have seen concerted efforts around Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) being added to the landscape of other blockchain based payment networks. On the other hand, we have also seen efforts such as that from the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) to replace its current settlement system--Clearing House Electronic Subregister System (CHESS) with a DLT based platform by 2021.

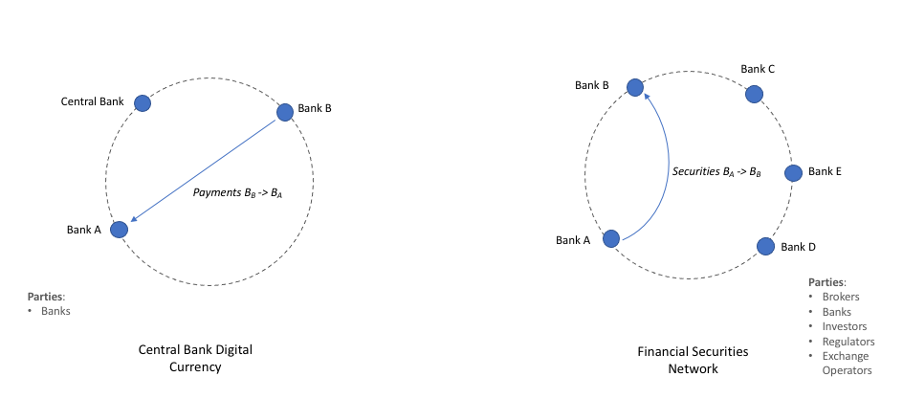

Against this backdrop, a number of central banks have been exploring the potential of performing DvP settlement across a currency ledger and a securities ledger. In this article, we use this as a motivating use-case for our discussions. The scenario involves two decentralised ledgers, namely, a currency ledger and a securities ledger, based on different DLT protocols performing a coordinated transfer of assets in their respective ledgers. Figure 1 depicts this scenario in the context of two organisations--Bank A and Bank B--in which Bank B wants to purchase some securities owned by Bank A and both organisations have accounts on both ledgers. To effect this exchange the following two transactions will have to happen atomically across both networks: i) transfer of payment from Bank B's currency account to Bank A while at the same time ii) the entitlements of the designated securities is transferred from Bank A to Bank B. The scenario would need to guarantee that after the transaction execution, either both parties have their end of the exchange or neither does and that this exchange is performed in a timely manner.

Figure 1. A typical DvP use-case.

Cross-chain transactions involving the movement of assets can generally take the form of either an asset exchange between parties or of value transfer from one network to another. The latter involves a scenario in which an asset in one network is locked or burned and a corresponding asset of similar value is issued in a corresponding network. This process generally involves validators or asset issuers in either or both ends of the network. While there are numerous use cases for this model in permissionless context, in this post we primarily focus on asset exchange scenarios, which are more broadly applicable in enterprise use-cases. Asset exchange scenarios generally involve two users swapping corresponding assets managed by the different networks, as in the example illustrated earlier. In asset exchange scenarios involving only two parties, both parties have accounts on both networks, although this might not be the case for exchanges involving more than two parties or networks.

Cross-Chain Asset Exchange on Public Blockchains

Similar scenarios that involve a pair of transactions being coordinated across distinct blockchains have been studied for public blockchains. One main application area is to enable decentralised exchange across crypto-currency networks. To achieve this, a number of cross-chain asset exchange protocols have been proposed. The original atomic swap protocol was proposed by TierNolan in the Bitcoin Forum. The protocol leverages trusted escrow services on both blockchains and relies on the asset owners for execution. Prestwich later improved the protocol by removing the trusted escrow services and using a smart contract to automatically execute the swap. Both protocols, however, are asymmetric and hence enforce a particular sequence of events. More recently, a group of researchers developed Arwen, which guarantees the symmetricality of the protocol and further eases the asset owners' responsibilities in the protocol execution.

We below first discuss the common patterns involved in the protocol design. More specifically, we present the main building blocks, core mechanisms, and security properties achieved by these protocols.

Building blocks

The design of a cross-chain asset exchange protocol in general contain the following building blocks: 1) the infrastructure for cross-chain state verification, and 2) the asset exchange protocol that specifies parties and sequences involved in the protocol execution. Cross-chain state verification can be performed by the exchanging parties themselves or by an external party.

Core Mechanisms

Fund locking: To initialise an asset exchange, it is common for one or both parties to first lock up funds with a fund-withholding party on his or her own blockchain. Temporary fund locking ensures the locked fund cannot be used for other purposes while the exchange is being executed. This scheme is often used with a specified timeout to provide flexibility for reclaiming locked funds if the exchange does not take place.

Fund redeeming: In general, the execution requires a pair of transactions to occur on both blockchains, e.g., from User A to User B on Chain A and from User B to User A on Chain B. When certain conditions are met, the locked funds can be redeemed by, or paid to the respective users. The execution of the exchange can be carried out by users themselves, or through other trusted third parties. These trusted third parties can be stand-alone parties that are not otherwise involved in both blockchains, or part of either blockchain.

Refund: For protocols that are initialised with a temporary fund-locking, the locked funds can usually be reclaimed by the initial owner after a specified timeout.

Security Properties

Atomicity: Atomicity is also sometimes referred to as safety. In general, atomicity implies indivisibility and irreducibility, namely, an atomic operation must be performed entirely or not performed at all. In the case of cross-chain asset exchange, when User A sends a payment to User B on Chain A, User B should also send corresponding delivery to User A on Chain B.

Liveness: Specifies the design of an asset exchange protocol should ensure no party can be tricked into locking up funds forever or for a very long time.

Extending Protocol Design To Permissioned Blockchains

Requirements of Permissioned Blockchains As public blockchains offer decentralisation and transparency, existing cross-chain asset exchange protocols on public blockchains are often designed for users to voluntarily participant and execute. To ensure secure execution of these protocols, their designs usually incorporate economic incentives, together with on-chain punishment schemes. To ensure liveness, these protocols usually leverage group consensus and fault-tolerance.

Permissioned blockchains on the other hand require privacy. Additional economic incentives and punishments are often not required besides the existing business relationships and established legal jurisdictions. Therefore, compared to public blockchains, the design of cross-chain asset exchange protocols on permissioned blockchains allows a higher level of centralisation and requires auditability and individual or group accountability for off-chain dispute resolution rather than economic incentives and on-chain punishments. Moreover, as permissioned blockchains themselves offer a higher throughput and faster transaction processing than public blockchains, the asset exchange protocol ideally should not introduce significant processing overheads that limit the transaction processing capability.

Therefore, the challenges in designing cross-chain asset exchange protocols for permissioned networks can be summarised as follow:

- Permissioned networks are usually confidential by design, thus restricting access for its internal members and external clients. State verification is hard to achieve across distinct permissioned blockchains. Cross-chain asset exchange protocols must therefore incorporate additional mechanisms to overcome these challenges.

- Unlike public blockchains, permissioned blockchains derive their security from and the ability to hold parties accountable for their actions. Any party acting maliciously should be identified and penalized during an off-chain dispute resolution process. Thus we can relax some of the constraints of the exchange protocol. For example, we can leverage trusted third-parties instead of having to financially incentivise regular users to participate in running the protocol.

Additional Properties

In addition to following the same set of building blocks, core mechanisms and security properties as public protocols, we also identify an additional set of desired properties for permissioned blockchains.

Scalability: Scalability is often restricted by two factors. Firstly, the transaction processing capability of the underlying infrastructures. When a protocol relies on public blockchains, the throughput is consequently limited by the transaction processing of the blockchains themselves. In contrast, some protocols are off-chain, which usually allow faster transaction processing. Secondly, for protocols that involve third parties for fund-locking, such as Xclaim and Dogethereum, the amount of money owned by these third parties limits the number of transaction requests they can process. As permissioned blockchains in general have a higher throughput compared to public blockchains, the protocol design should not trade off scalability.

Auditability: Auditability for public blockchains specifies that any party with read right should be able to detect protocol failure. On permissioned blockchains, however, as parties have limited visibility over the ledger state, who can detect protocol failure will most-likely depend on the use-case. In addition, financial regulatory requirements such as AML and CTF might require cross-chain traceability and auditability of exchange transactions (i.e. it should be easy to trace why Alice just transferred Bob $1M on a CBDC network).

Accountability: Accountability says faulty parties should be held accountable. This can refer to individual accountability or group accountability. As it is hard to enforce on-chain punishments on permissioned blockchains, the protocol design should at least allow adversaries to be held accountable.

Compatibility: Compatibility specifies how easy it is to implement the protocol on other blockchain platforms. The protocol design should be generic and not to be limited to particular blockchain platforms.

Extensibility: Extensibility specifies how easy it is to extend the protocol to other use cases, for instance, from two parties to multiple parties, or from one particular transaction pattern to other transaction patterns.

Privacy: Privacy is usually not automatically guaranteed by public blockchains. For sensitive use-cases, extra mechanisms such as a trusted execution environment (TEE) can be used. Privacy is also of vital importance when it comes to permissioned blockchains. Most existing cross-chain protocols are designed for public blockchains. As the execution of these protocols may require asset owners or third-parties to access states on either blockchain ledger, executing a cross-chain asset exchange can put user privacy at risk.

Low Cost: As many of the cross-chain exchange protocols involve sending on-chain transactions, the concern over number of transactions and transaction fees arises when the protocol design involves a public blockchain.

Conclusion

To summarise, in this article we tackle the problem of enabling cross-chain asset exchange on permissioned blockchains and evaluate the different requirements imposed by public blockchains and permissioned blockchains. We also articulate a set of desired properties to guide the design of cross-chain asset exchange protocols.

For general-purpose interoperability of enterprise blockchains, we have developed the Weaver tool that incorporates a cross-chain state verification engine to enable cross-chain state sharing and verification. Please check out our documentation for implementation details and example applications.